The time evolution of star forming cores

With Dr. Kaitlin Kratter, Dr. Stella Offner, Dr. Aaron Lee, & Dr. Hope Chen

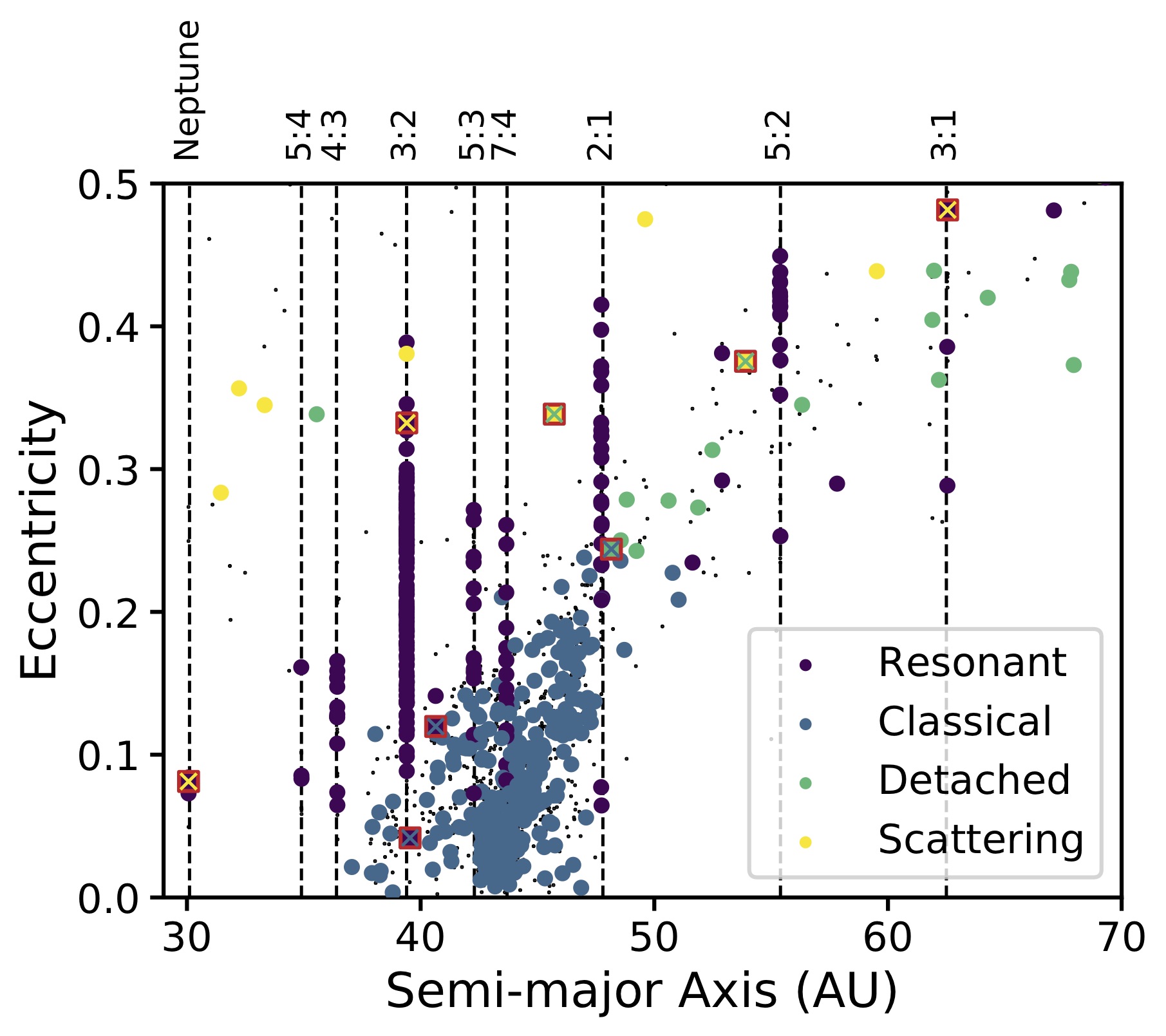

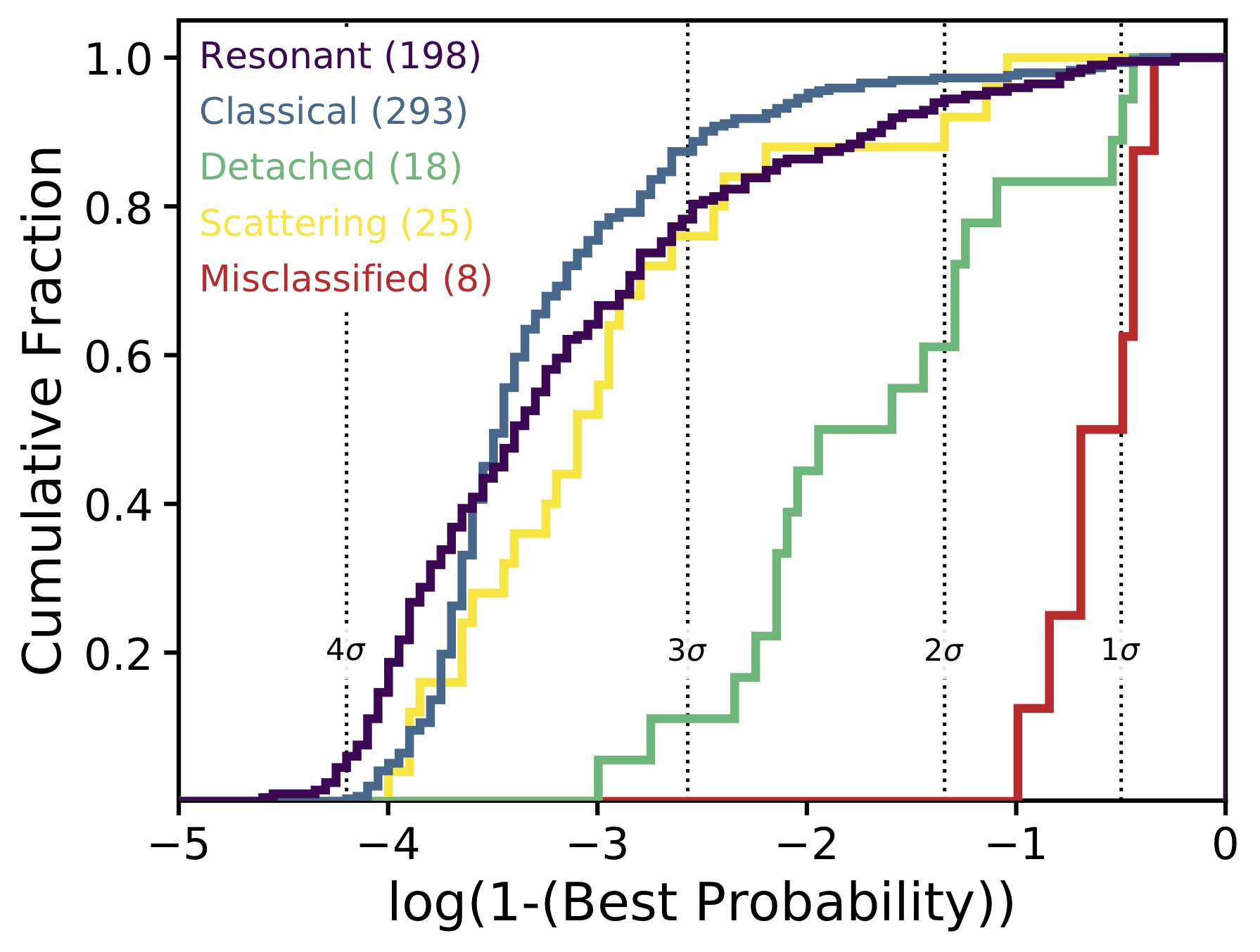

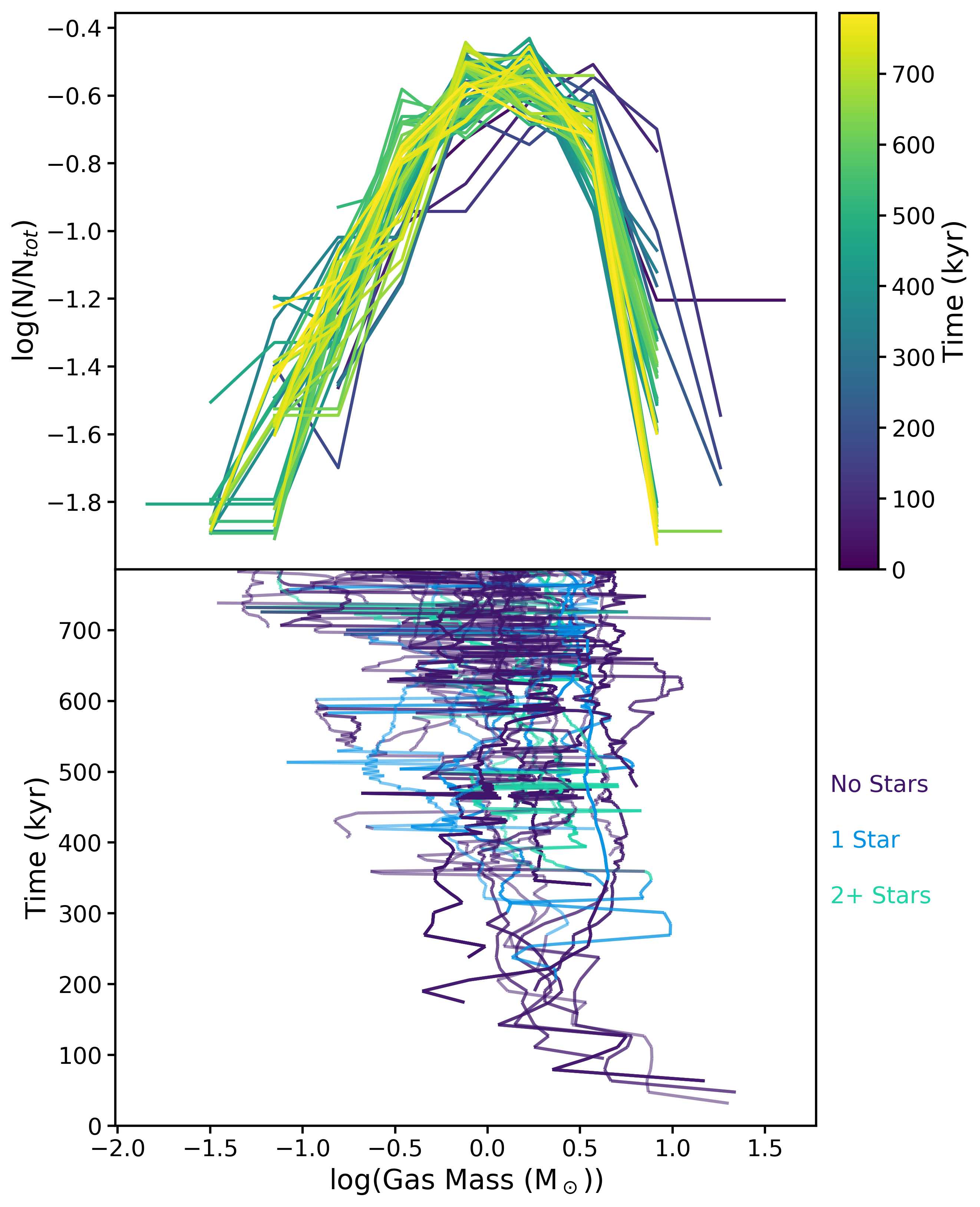

Top: Movie of projected density. Pink circles are single stars, blue circles are in multiples. Bottom: Distributions of core gas mass as a function of time (top panel) against the time evolution of individual cores (bottom panel). The distribution of core masses is nearly time independent, while individual cores undergo significant variability on short timescales. |

Observations will never be able to study the long-term evolution of individual cores. We therefore aim to understand time-resolved core evolution using hydrodynamical simulations of a low mass star forming region. We want to better inform the big picture of the star formation process and show how individual snapshots relate to the time-varying evolution of cores.

Thus, we conclude that there is no time-stable density contour that defines a bound core. Because of the dynamic nature of core evolution, a single set of dendrogram parameters will not trace unique core parameters across the entire lifetime of core formation. Additionally, despite large variation in individual core properties, the overall distribution of properties evolves little in time; this contradiction call into to question the correspondence between individual core properties and the stars they produce. |

This paper is under review at MNRAS and can be found on arXiv: 2004.01263